Tokyo Towns: The Characters of Akihabara

Part 2 of 3: Face to face with the Power of the Character in Tokyo's otaku mecca

[Hello, I’m not dead! In the last two months I got a new job and moved into a new apartment, so I’ve been way busier, and was thrown off my old writing schedule. This post also took some extra effort from all the links and references. Thanks for being patient, here is your reward!]

Akihabara, or Akiba for short, is an area in central Tokyo that is also called “Electric Town”. Wikipedia says it gained this reputation in the wake of World War II, as the place to get household electronics and appliances when (re)building homes. This is still apparent in force today: plenty of tiny shops here are packed with secondhand electronics of all kinds—but interestingly, even more places sell simple electronic components. Loose motors, circuit boards, spools of wire, and all sorts of spare parts and tools were arranged across shelves and tables, with no empty space, in shops crowded together along entire city blocks. It made me happy to see how easy it was to dig into, for anyone passionate about electronics, tinkering, or just the right to repair.

But this isn’t typically what draws tourists to Akihabara. You see, as time moved past the postwar era, shiny newfangled home appliances became less exciting, and made way for home computers in the ’80s. The new customer base tended to thus be computer nerds, who also enjoyed manga, anime, video games, and the like. Those obsessive geeks became known in Japan, somewhat pejoratively, as Otaku. As they were the main clientele, Akiba was a natural fit to then become a hub for their favorite media as well: Why get a console or TV without something to play or watch, after all? It didn’t take long after that for the media itself to grow its own roots, flourish, and give Electric Town a whole new meaning.

Today, Akiba is the global mecca of Otaku culture (in other words, anime, manga, video games, trading card games, vocaloids, VTubers, and more), and it’s quite self-aware of this identity: one day I walked by a tour group on the street, and the tour guide was holding up and explaining a cartoon image of a stereotypical Otaku on it (see below). Otaku culture itself has spread and gained massive popularity across the whole world in the last thirty years, especially anime. There’s even a newer term from Internet slang to describe foreigners with Japan-obsessed Otaku sensibilities: weeaboos, or weebs for short (it’s still somewhat pejorative).

Exactly what happened to make Otaku stuff so popular over the past few decades is a deep topic that would require a well-researched post of its own, but today it’s nigh unavoidable. Movies and TV shows worldwide, both animated and live-action, take constant inspiration from foundational anime like Dragon Ball Z or Akira for their action style and choreography. Many famous rappers, like Denzel Curry or Lil Uzi Vert, look to anime for lyrical and aesthetic inspiration. The rapper Megan Thee Stallion is a self-proclaimed “Otaku Hot Girl” and takes it even further, wearing anime cosplay, and speaking at this year’s Anime Awards. This year, McDonald’s pushed an anime-based ad campaign, and did cross-promotion with actual anime shows, both for American audiences.

But to truly see the global influence of anime and Otaku culture, there’s perhaps nowhere better to look than the recent mourning of manga artist Akira Toriyama, the creator of Dragon Ball Z. After his passing on March 1st of this year, thousands gathered in Argentina, a massive mural was made by dozens of artists in Peru, and countless celebrities in music, film, and sports all shared their condolences—including government officials like the president of France and the foreign affairs ministries of China and El Salvador. It’s not just for geeks or Otakus or weeaboos anymore. Anime’s cultural influence is universal, and Akiba is its nexus.

Otaku culture’s mass appeal, however, is just the latest incarnation of a gigantic aspect of Japanese culture as a whole: The Power of the Character. I mentioned it briefly in previous posts, but I think it’s time to finally get into it.

The Power of the Character

It’s kind of impossible to nutshell, but if I were to try, I would say the Power of the Character is the prevalence and influence of characters—single beings with a distinct appearance and/or personality—to personify some greater concept that they belong to. At its core, it’s just anthropomorphism, which is a universal aspect of all cultures—we humans just can’t help but empathize with things—but what makes Japan’s version unique, and capital-P Powerful, is a few things:

Its vast scope. Everything in Japan has some character associated with it, not just the entertainment industry. Brands of course, but also NGOs, government agencies, cities, law firms, train lines, restaurants, you name it.

Its strong personality. Characters often resemble what they represent, naturally, but Japanese characters tend to have a couple core personality traits thrown in as well. This adds even more empathy and helps them stand out in the crowded character landscape. Gudetama, for one example, isn’t just a cute egg, he’s also very lazy and likes lying around.

Its idealism. The vast majority of these characters are cute, strong, beautiful, or some combination of the three (but mostly cute, thanks to kawaii (かわいい) culture). They are pretty much always shown in a friendly, positive light. If they have any negative traits, they’re endearing (see #2 again). On top of that, something else interesting happens here: because of this abstraction from reality, even real people can brand themselves this way and become character-like, building their character’s persona above and beyond their own humanity. So with the same techniques that a mascot may bring its parent company’s image closer to human, actual humans are going further away, up towards imaginary ideals.

What could have caused Japan of all places to develop such a love affair with characters and personalities? Part of the origin story goes all the way back to the beginnings of Japan, and the culture of its prehistoric peoples. In ancient days, the religion and folklore of the land focused on animism: the idea that everything in the environment has a spirit, a soul, an essence—and with it, a personality. (This was also a large aspect of early indigenous folklore in many places around the world, especially Asia and the Americas.) You may recall from my Ise Jingu post about the kami, from the Shinto religion: sacred spirits that embody everything, from the sun, to a strong wind, to the memories of an ancestral clan. Well, on the flip side, folk tales are also abound with yokai, quirkier supernatural beings that often represent the unexplained (similar to ghosts in American folklore). They vary wildly in form and personality, but they’re usually at least shape-shifters with a penchant for mischief. They can be animal based, like a kitsune (fox) or a tanuki (raccoon dog), or object-based, like chochin obake (“lantern ghosts”). They can be a whole class of creatures, like the demonic oni, or totally unique, like the territorial, turtle-like river creatures called kappa who love cucumbers and sumo wrestling. There are hundreds, if not thousands of them, and it’s an easy rabbit hole to get lost in. If you’re interested, check out the extensive database over at yokai.com!

The animist mythos of the kami and the yokai has had a strong influence on Japan over time, one that has been carried through the ages. You might expect the influence of folklore to die out with the growth of modern industrial/technological society, as it sorta did in Europe and America. But instead, it found a new niche: marketing. Japan has known this whole time how great personification is as a way to connect to an abstract concept—and once they had a booming economy to handle, it only became natural to personify organizations, products, companies, and brands into personified characters as well! It’s capitalism gone kawaii!

And that leads us straight to today, where Japan’s cultural landscape is shaped by its exaltation of mascots, idols, and characters one and all. I encountered an absolute plethora, an utter myriad, a complete f*ckton of examples on my trip, in Akiba and elsewhere. Here’s a bunch of the ones that I could remember; you can think of it as a small survey of the Japanese character zeitgeist.

The Characters

Otaku merch tends to focus heavily on the characters from their respective shows/video games. Figurines and plushies were literally everywhere in Akiba, and slightly less everywhere in other cities. Among the franchises I saw most often were One Piece, Dragon Ball Z, Spy X Family, JoJo’s Bizarre Adventure, Neon Genesis Evangelion, Naruto, various Studio Ghibli movies, Chainsaw Man, Jujutsu Kaisen, Haikyu!!, My Hero Academia, Demon Slayer, and Slam Dunk, but there really is something for everyone. (And those are just the ones I recognized!)

Character Brands are insanely popular, and often very cute (kawaii かわいい). The two titan companies of cute characters are called Sanrio and San-X. San-X owns many adorable, characters, such as Rilakkuma the relaxed teddy bear, a line of shy characters called “Life in the corner“, and many more. Sanrio has their own roster as well, including a long-eared dog(?) named Cinnamoroll, and that lazy egg Gudetama—but their biggest draw by far is the very poster child of kawaii culture: Hello Kitty (Who has also acted as Japan’s tourism ambassador!)

Not every character is affiliated with megacorps though. There were some independent brands too: there’s Pusheen, a round grey cat who started as a webcomic; Pandorobou, a rat who steals bread and wears it; or the adorable lifelike kittens of Mofusand.

Several popular characters stem from children’s media instead of directly from a company’s roster: robot-cat Doraemon and little boy Crayon Shin-chan are both from old manga/anime series, but have jumped off the page to show up all over the place. Doraemon has also gotten the ambassador treatment, for animation.

If they’re kawaii enough, the character may not even be from Japan. European children’s characters like Moomin and Miffy, as well as American ones like Snoopy or Tom & Jerry, were all present in force, held in higher reverence here than even their home country.

Some brands are big enough to have their own physical stores. Sanrio is one; they have a few physical locations in parts of Tokyo. Studio Ghibli also has a popular brand shop with multiple locations. And I already showed you two others back in Shibuya, whose trademark characters are among the most famous of all time: Nintendo and Pokémon.

Smaller / foreign IPs will also have brick-and-mortar shops, in certain character-focused shopping streets. Character Street below Tokyo Station is one, and Sunshine City Mall in Ikebukuro is another. And of course, Akiba is one as well. I saw every IP I listed earlier represented, plus even Marvel and Sesame Street.

Mascots, mascots, mascots! Again, if the yokai have taught us anything, it’s that abstract ideas can become very powerful when given a name and a form. The more of Japan you see, especially in city centers and train stations, the more it feels like there isn’t a single place, event, or organization, public or private, without their own promotional mascot. In this context, they have their own name: yuru-chara (ゆるキャラ), abbreviated Japanese for “laid-back character”.

Two big examples: Domo (for NHK, Japan’s public broadcast company) and Kumamon (for the Kumamoto prefecture) are two yuru-chara whose likenesses and merch have become popular in their own right.

One such mascot, named Chiitan, has become semi-famous in the West, and online, thanks to John Oliver. Chiitan started as an unofficial yuru-chara for the city of Susaki, and their absurd, mildly violent internet presence led to some controversy. Oliver covered the story for his show Last Week Tonight, and made a companion mascot named “Chii-john“. Chiitan is now a viral phenomenon, still quite active—most recently, they’ve taken to buying up ad space on Twitter just to push out real ads and show more funny videos instead. Which I appreciate.

Pokémon has even crossed over into this ‘civic mascot’ space: Pokémon Local Acts is a program that partners certain prefectures in Japan with “ambassadorial Pokémon” that best match their attributes. For example, Mie Prefecture is coastal and known for its seafood, especially shellfish—which makes Oshawott, an otter-based Pokémon with a seashell on its stomach, a perfect fit. Back in Ise Jingu (in Mie), I saw lots of Oshawott merch, and even an Oshawott-themed train car.

If you want even more, Mondo Mascots is a social media account dedicated exclusively to documenting Japan’s mascots. There are so many great posts there, documenting so many unique local yuru-chara, to the point where it ought to be considered an Internet World Heritage Site. Please check it out!

As we discussed, a real-life person can also become a character! Often I would see ads depicting people with exaggerated faces/outfits repping their company. It felt similar to how small, local American businesses will occasionally have eccentric human ‘mascots’. Larger than life, but still rooted in being real people.

Above the local level though, a big enough character-ized person becomes something totally new: an idol. Idols are another huge tenet of Japanese (and Korean) entertainment culture, over which much ink has already been spilled, but simply put, the level of idolatry in the industry on this side of the world is unparalleled. Like the character brand shops, entire shops exist just for photos of the idols on posters, prints, magazines, etc. Like I mentioned before, there are some key differences between the power of the character vs. the power of the idol—the former is used to induce empathy and get closer to apparent humanity, where the latter is more idealistic/aspirational, aiming above and beyond humanity—but it’s in stores like these, in towns like Akiba, where the lines between them will feel really blurry. From inside the shops, densely packed with shelves of merch and rabid fans, they feel pretty much the same.

Not a real human, but a unique case worth mentioning: Even something as abstract as software can become an idol character, in the case of Hatsune Miku. “She” is a synthetic voice program designed by Crypton Future Media for music-making purposes, but their genius idea was to market the voice with a name and a face alongside it, turning it into a whole character. Internet memes of her likeness then went viral, her songs got popular, and she was cemented as an icon of J-pop music, where she remains today. She even does live concerts with a projector and a screen, as she did at Coachella this year.

In the last decade or so, Japan has also developed a new type of hybrid virtual idol, called a VTuber (like Virtual YouTuber). This is a person who does streaming-based content online, but their real-life movements and facial expressions are captured and mapped onto an anime character model. This virtual mask smudges the line between a real-life streamer, an anime character, and a mascot in an outfit. They gained some traction in 2020, streaming for everyone in quarantine, and it’s become popular enough that there are now huge, official agencies representing VTubers. One of the biggest such agencies is called Hololive: they have 90 VTuber talents with a collective 87 million followers, and made ¥30 billion ($200 million) last year. There was even a Hololive Night recently at Dodgers Stadium, where they sang songs and did a drone show. Back in Akiba, there was tons of shop space dedicated just to VTuber merch—nearly as much as all the anime stuff combined!

Characters are everywhere in human culture, but in Japan they are a deep-rooted institution. And because there are so many here, each one is pushed to be as unique, expressive, and vibrant as possible, to stand out in the crowd. We can’t help but relate to their overt, endearing personalities, which has made them expand to a global cultural influence, with no signs of slowing down. The old storytellers who first wrote about the yokai would probably not be able to fathom it all. Even people today can find it overwhelming. But I’ll bet they would still appreciate the shyness and sweetness in each kawaii character, the relaxed whimsy of each yuru-chara, and the charisma and star-power of each idol. After all, they were just like us: empathic human beings, experiencing the world by seeing bits of themselves in it.

Gacha: How They Getcha

Akihabara’s Electric Town reputation for tech and entertainment, combined with its merch-driven tourism, can only mean one thing: tons of arcades, with plenty of games chock-full of little plastic prizes, usually anime merch. Like back in Nagoya, these arcades were arranged by category: rhythm games on one floor, fighting games on another. The crane/prize games were always right at ground-level though, flashing and blaring to get you to drop in some yen. My friend was a huge fan of a punching game with progressively bigger foes: First a simple bank robber, then a semi truck, then a T-rex, then a meteor. I personally had the most fun playing the Taiko no Tatsujin (“Drum Master”) drumming rhythm game. Which, surprise surprise, has a cute mascot named Don-chan whose plushie I could win from the crane games downstairs.

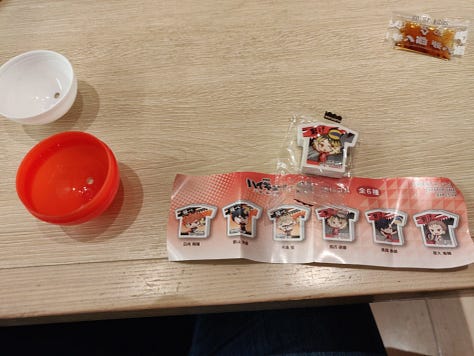

But there’s one type of ‘game’ in Japan that you won’t find much of in arcades, because it’s already everywhere else. It’s called gacha, aptly pronounced like “gotcha!”, and it’s a simple capsule-toy machine. Drop in some yen, turn the crank, and out pops a little something in a plastic capsule. (The equivalent in America is those gumball-type machines in the antechambers of arcades, movie theaters, etc, and they have those little parachute soldiers or bouncy balls or sticky hands.) Their appeal in Japan is in the gamble: Each machine is loaded with a specific set of prizes, so you’re guaranteed to get 1 out of ~4-6 different items, but it’s random which one you get. Some prize sets will belong all-together, so you’ll want to collect them all, and some sets have extra-rare, extra-cool standout items that may only be in one capsule in the whole machine. Both of these tricks hook people even more, and it’s not long before they’ve gacha.

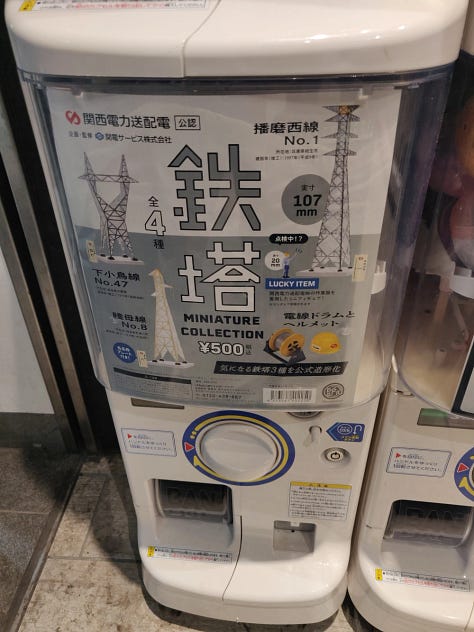

I cannot stress enough how these were located everywhere: arcades, train stations, outside konbinis, in parks, restaurants, museums, in dedicated gacha stores, or just out on the sidewalk. They also contained everything you could imagine, in miniature. Of course there were plenty of characters from anime and stuff, naturally. Even characters from more niche media like Undertale or the Suika Game were present here, since I suppose gacha merch is the cheapest kind to make. Many were animals, mostly cute, a few realistic. Many were matchbox cars. Lots were mini foods and drinks, which I thought were adorable. There were a few weird gimmicky ones that felt like they’d be in a cereal box, like a skull-shaped ring that opens a little coin bank, or a wristwatch made to look like a bathroom scale(?). But a shocking amount of the gacha prizes were actually just everyday mundane items, as a keychain or figurine. Some actual gacha machine prizes I saw included: Furniture sets. Train signs. Button labels. CDs. Levers. Cleaning products. Airline food, in the tray, sponsored by the airline. Even literal telephone poles were a mini gacha prize. You could populate an entire village of dollhouses, and a model train set to connect them, with enough time and coins.

So, is it bad that these are everywhere, pushing kids to gamble? I thought so at first, but now I have no idea. Japan doesn’t appear to have a significantly high gambling rate among all nations. Heck, maybe for some, getting exposed to it as a kid lets you see how much of a rip-off it is before you’re spending real adult money at the Pachinko machines, sorta like a vaccine—but that’s wild speculation. All I can say for sure is that I’m not immune: I definitely got hooked a couple of times and wasted a bit of yen just to get the coolest prize—the biggest culprit being a Pioneer-brand DJ-equipment gacha machine. I couldn’t help but obsess over the miniature record player and speaker sets, they were so cute and detailed!

The “gacha” model has also gone digital in the last decade. A genre of video game called “gacha games”—where you put money into a virtual gacha machine for a random character/item that you then collect and play with—is now immensely popular, employing the same basic gambling principles. If anything, I would be more worried about these ones, unmoored by a physical form, able to hook you at home. Genshin Impact, perhaps the most popular gacha game at the moment, set a record for the fastest mobile app to hit $5 billion in revenue as of this year. I wonder how much of that $5 billion resulted in the players actually getting the character or item they wanted. Remember, folks: The house always wins.

One last, unrelated tidbit: Akihabara was also, apparently, the place to find the most adult entertainment shops. This is yet another thing that I saw in all Japanese cities, but I saw the most here in Akiba. And again, sex culture in Japan is a very deep topic, deserving of its own post. But in a nutshell, it seems like there’s much less sexual shame in the culture here, more embracing of kinks/non-standard preferences, and more stuff made for women. Otaku and anime culture intersect here as well, with tons of manga/anime shops having extensive 18+ sections behind thin curtains. And that is where I’ll leave this topic, because my family reads this blog.

The next entry will be the last Tokyo Towns post, before I start to close out my Japan series. Now that I have a day job again, I will probably only be posting ~once a month, but I should be more consistent now. As always, thanks so much for reading!